How Evolutionary Theory Explains Transphobia

Hint: It has to do with penises.

This article was originally published in Le Point on 06.29.2025

While it seems the whole hot-headed world has had its knickers in a twist over what is a woman and who should be allowed to use that label, a team of psychological scientists from the University of Perugia in central Italy have arguably taken a more measured approach. Stefano Federici and his colleagues have been trying to pinpoint just what features of another person’s body, exactly, cause us to perceive them as male or female.

The answer may seem rather obvious, given anatomical differences. But as it turns out, it’s a lopsided equation. When it comes to our most primal reasoning processes—and I didn’t think I’d ever put things quite this way—penises are much more powerful than vulvas.

But let’s back up a bit. First, doing research on the cold cognitive mechanisms behind “gender attribution”—effectively, what observable features, or combination thereof, lead us to confidently judge another adult human being as a man or a woman—doesn’t involve taking any position at all on issues of transgender rights and/or feminism. Still, such research is of great relevance, I think, in helping us to understand the psychology behind those incendiary debates. In fact, Federici’s theoretical framing also sheds much-needed light on why people react so strongly over who gets to be called a woman when, comparatively speaking, they mostly just shrug their shoulders over who gets to be called a man.

That disproportionate emotional response, argue the authors in a 2022 study published in Archives of Sexual Behavior, reflects an adaptation shaped by our species’ evolutionary past. Yes, “man is the most dangerous animal of all,” as the expression goes, but the key part of that sentence is man. To state a scientific truism, biological males in every society and in every historical period were—and are—significantly more prone to physical and sexual violence than biological females.

With that unequivocal fact in mind, reason Federici and his coauthors, the “cost” of mistaking a man for a woman (effectively, failing to detect a potentially dangerous threat in the environment and lowering one’s guard) would be dramatically higher than the reverse. So, because males posed a far greater danger to everyone in the ancestral past—men, women, and children—the human mind evolved to be hypervigilant to markers of the male sex.

Evolutionary psychologists refer to this type of weighted cognitive bias and attentional readiness as part of a so-called error management system. The idea is that our psychology was forged, not so much to perceive reality as clearly as possible, but instead to err on the side of caution when faced with ambiguous, confusing, or missing information. This meant making split-second judgements that were often flat-out wrong but nevertheless minimized risk and maximized our reproductive and survival outcomes. It’s much more costly to mistake a snake for a stick than a stick for a snake, or to assume that a leopard is dead when it’s just sleeping than the other way around. Error-management theory has also been used to explain why men overinterpret (or misinterpret entirely) women smiling at them as a sign of the latter’s sexual interest, when it’s more likely she’s just being polite and would smile the same way at a curious squirrel. From the gene’s-eye view, it’s better to seize on a possible mating opportunity than to miss it altogether.

In the current context, rapidly discerning a person’s sex would have been a core adaptive problem, and all else being equal, it’s safer to assume male than not. “Consistent with the evolutionary perspective,” reason the authors:

this mechanism has developed to avoid what is the greatest danger: an (angry) adult male. In addition, because people rely on simplifying the decision-making process, especially in cases of ambiguity, time pressure, or complexity, they revert to heuristic strategies. The human being must at all costs avoid confusing a male for a female, rather than the opposite. Lowering one’s defenses, because one has assumed to be in the presence of a female rather than a male, is more likely to cost one’s life compared to confusing a female with a male . . . humans have had to avoid at all costs a false negative (detecting a female when it is male) because it is definitely riskier than a false positive (detecting a male when it is female) . . . In other words, to survive, it is much more convenient to make a wrong female than a male gender attribution.

Previous research indirectly supported this line of reasoning. Brain studies reveal that we automatically dichotomize faces based on gender at a staggering speed (in milliseconds, nearly as quickly as grouping strangers into “us/them” by race), and it’s much easier to evoke a fearful emotional reaction when participants are shown photos of angry male faces than female ones. But Federici and his team wanted to address this possible “male recognition bias” directly, and the best way to do that, they figured, was to present participants with a wide range of images depicting digitally blended configurations of an archetypal adult male with an archetypal adult female, and asking, “according to you, is the subject in the picture male or female”?

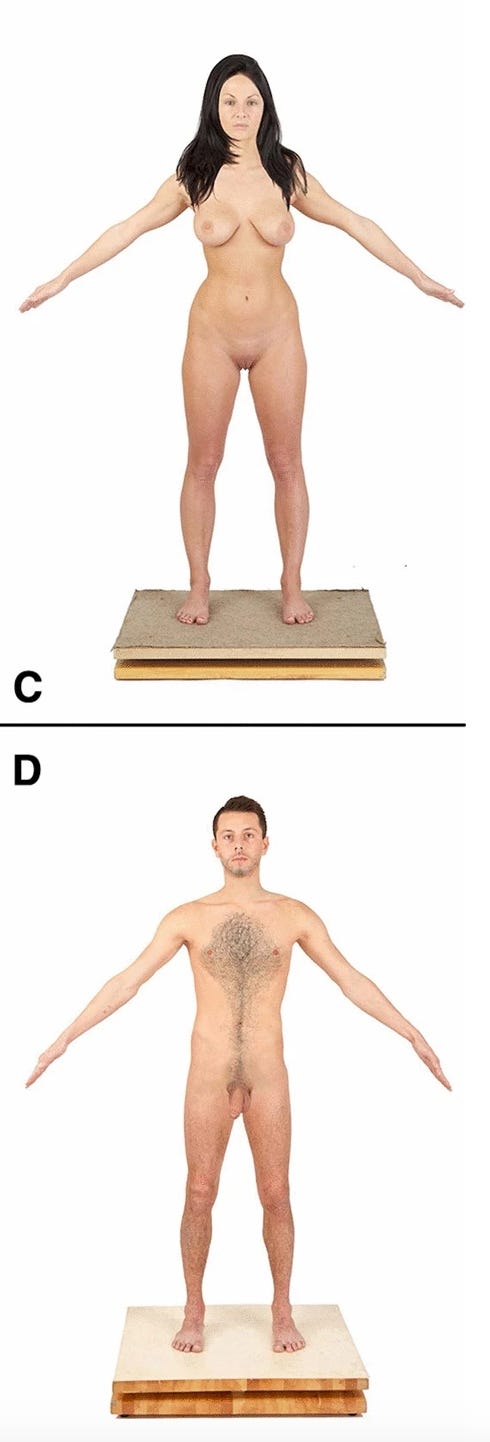

The first step was therefore to find the perfect Adam and Eve to use for the photo stimuli fodder, a naked man who best matched people’s mental image of “biological male” and a naked woman who did the same for the female form. (An earlier study from the 1970s used line drawings with overlaid stenciled body parts, and the authors wanted more realistic material.) In the pre-experimental phase, 200 random Italians were shown 20 front-facing anatomical nudes (think Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man pose): 10 individual male models and 10 female models, all sourced from the same stock photography website. The image of the male who was judged by these raters as the “most masculine” and the female seen as being “most feminine” were then used for the actual study, where, in a mix-and-match gender picture show, these models’ primary and secondary sexual characteristics were morphed systematically to produce every possible physical combination as a single target image.

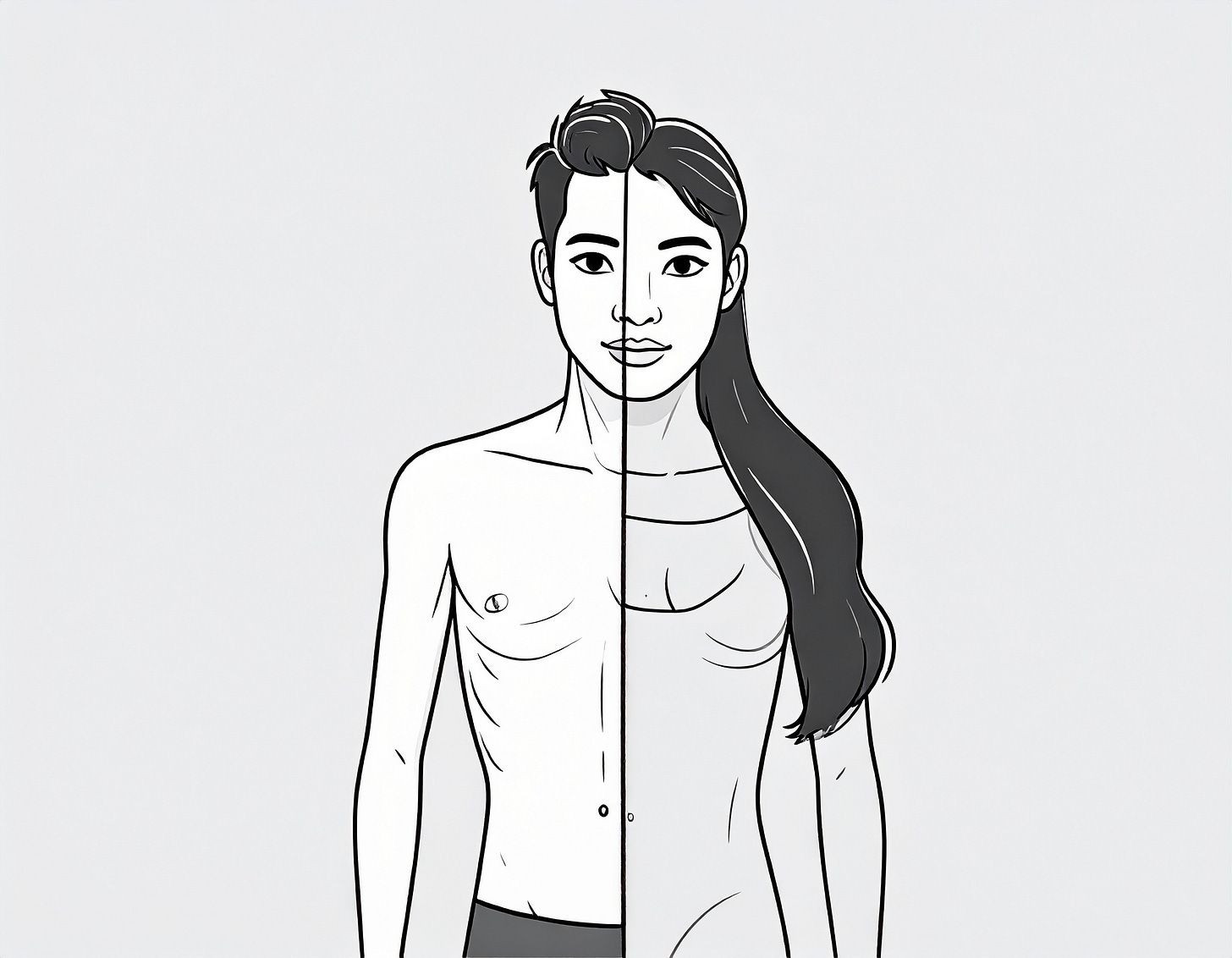

The researchers were careful to distinguish between primary sexual characteristics (penis or vulva) and more variable secondary, gender-linked sexual characteristics, such as distribution of body hair and facial shape. In the end, they isolated 6 discrete male variables (short hair, male face, flat chest, narrow hips, penis, body hair) and 6 female variables (long hair, female face, breasts, wide hips, vulva, no body hair). Adding two pieces of photoshopped unisex clothing (t-shirt, jeans)—there were also various stages of undress, from flaccid penis blowing in the wind or tucked inside digital Adobe pants, breasts liberated or covered up, to every questionable fashion pairing in between—this created 120 shots total, each designed to capture gender as a discrete tick mark on the physical spectrum. Just to give a few examples of what that looked like, then, in one image the topless target has the male face, long hair, breasts, body hair, is wearing pants, has wide hips, and so on, whereas in another, the pantless target has the woman’s face, is wearing a shirt, short hair, has a penis, narrow hips, and no body hair. And so on.

In the main experiment, participants were given a simple set of instructions. On the screen in front of you, they were told, you’ll see a random succession of images of a human being. Some of these images will be nudes, whereas others will show a person in clothes. For each image, you’ll be asked three questions. Is the person in this photo male or female? How confident are you in that judgment? How pleasant do you find this image? The first question was forced-choice—male or female. The other two, by contrast, were on a Likert-scale, which means they measured degree of confidence and pleasantness.

Nearly 600 undergrad participants completed the 40-minute task. Importantly, these raters included an equal proportion of males and females (and even several nonbinary participants), of all political persuasions and religious stripes. None of those things mattered one bit to the results, it turns out. There were no differences between them in perceiving male or female.

Based on the logic of error management theory, the researchers had several hypotheses, all of which—spoiler alert—were indeed confirmed by their findings.

First off, given that “better safe than sorry” rule of thumb in assuming male in the face of ambiguous or confusing cues, they predicted that participants would make significantly more male attributions overall. This general effect panned out. On average (across all participants rating the 120 images), people judged the subject in the photo as male 60.1% of the time, and as female only 39.9% of the time.

Next, Federici and his colleagues reasoned that primary sexual characteristics (again, those dangly or not so dangly bits below) would hold more sway in people’s gender judgements than secondary sexual characteristics. Exceptions occur more often than many assume (about 1.7 percent of the population is intersex), but genitalia are still an overwhelmingly reliable marker of a person’s sex. Moreover, it’s one thing to acknowledge the complex biological reality of chromosomal abnormalities leading to intersex conditions, or even to challenge simplistic gender binary models, and another to study the trigger-happy psychological mechanisms fitted out by natural selection to solve the “male problem.” Secondary, gender-linked sexual characteristics are obviously much more variable, influenced by cultural factors (e.g., hair length), heritability (e.g., hip width), or often both (e.g., body hair).

And again, when it came to the study’s results, bingo. “When genitals are displayed,” write the authors, “[gender] attribution is congruent with the stimulus gender about two times more than when only secondary characteristics are shown.” In other words, when all you’ve got to go on is a vulva or penis, people are much more likely to ascribe gender consistent with that sex organ (penis = male; vulva = female) than when you’re dealing with only those slippery secondary clues. In fact, when the genitals were covered up entirely, gender attribution was congruent to the hidden sex organs only 47.4% of the time.

But there are two important qualifiers with the points above. These the authors refer to as the “penis effect” and the “male face effect,” the two most powerful drivers of gender attribution. Let’s, um, look at the penis first. “When the penis was exposed in the picture,” explain the scientists, “the participants attributed male gender about five times more often than female gender when the vulva was exposed.” Moreover, the participants were much more confident they’d gotten their gender attribution judgement right if a penis was involved than a vulva. People are more able, it seems, to entertain the queer-friendly idea that gender is not just genitalia for a person who has a vulva, than they are for a person with a penis.

A similar imbalance was found in the potency of the male face compared to the female face. Basically, when the participants saw a male face sans penis, and regardless of the presence or absence of other secondary characteristics (breasts, wide hips, and so on), they were 1000 times more likely to see a man than if they saw a female face sans vulva (but with a flat chest, narrow hips, etc.). And it’s the penis, that dreadful slug, that concupiscent beast, that can “nullify the presence of a female face.” When you put a male face together with a penis, well, it’s apparently next to impossible for the human brain to see anything other than a man. That testosterone-fueled pairing can “overshadow all other female cues,” write the authors.

As for that third question posed to participants, about how pleasant or unpleasant they found each photo to be, you can probably guess, sadly, what the evidence showed. Of the 20 gender neutral photos displaying a balanced co-presence of male and female characteristics, 98% of people found them unpleasant, a significantly higher percentage than for all the other (unbalanced) images. The authors venture some guesses as to why people found these physical combinations so uncomfortable, but they land on the idea that the ambiguity of the target induces a sort of cognitive unease; the adaptive mechanisms designed to rapidly categorize others as “male” or “female,” and which are mentally gratifying when deployed effortlessly, are disrupted by figures with ambiguous or conflicting sexual characteristics. This is epitomized—and to many, painfully so—by that old recurring Saturday Night Live skit featuring Julia Sweeney as the androgynous “Pat,” where the entire shtick centered on the frustrated efforts of those trying every possible gambit to decipher Pat’s sex.

The authors’ takeaway from this line of reasoning is that negative attitudes toward trans or nonbinary people are largely due to a “system error” in the perceiver’s Pleistocene-cobbled brain, one that presumably induces feelings of negative affect. Federici and his colleagues, for their part, do not minimize the caustic, and indeed distressing, levels of bigotry against these marginalized individuals, but instead see their findings as essential to helping to alleviate such blind hatred, given that it’s typically perpetrated by those entirely naïve to their own evolved psychology. “[This theory] captures processes of psychological functioning,” they write, “which reveal to us cognitive mechanisms at the origin of cultural biases.”

We believe that the cultural stereotypes and prejudices that lead to sexual discrimination and oppression are not a mere and arbitrary cultural product, but the consequence of cognitive biases. This, far from justifying human behavior because it is biologically determined, must help us understand why, after millenia of civilization, gender discrimination resists cultural progress . . . Gender equality requires historical remembrance and education on the salience of male sexual characteristics.

In a follow-up study published in Scientific Reports, Federici’s team replicated their findings, this time with a large Chinese sample (1706 participants). They also included a measure of latency: how quickly participants assigned a sex to the person in the photo. As expected, participants were fastest in rendering a judgment when male characteristics were shown.

In my view, it’s a pity this, ahem, body of research isn’t widely known and understood, as evolutionary logic could surely throw cold water on fiery, often irrational, public discourse.

Like what you read? Toss a tip in the jar—any amount that makes sense for you—so I can keep overthinking things on your behalf.

Minor correction-- the 1.7% is for people with DSDs, most of whom have an unambiguous sex (this has been misrepresented ad nauseum by political organizations). The actual percent of intersex people, in any sense relevant to this article, is two orders of magnitude smaller: https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490209552139

This seems very plausible. I had chalked it up to sort of an uncanny valley effect where we can’t quickly sort a person into one of the sexes but I didn’t know about this preceding step for that discomfort.