Does Environmentalism Have an "Effeminate" Branding Problem?

Implicit threats to masculinity negatively affect men's green decision-making

This article was originally published in Le Point on 09.11.2025

There was no end to the stark and worrying facts to emerge from the United Nations COP30 climate change conference in Belém last month. With global temperatures rising to 1.42°C above preindustrial times, and 2025 officially the hottest year on record, the world is now very close to exceeding the 1.5°C warming threshold—a limit recognised in the Paris Agreement ten years ago. Crossing it would significantly raise the risk of triggering tipping-points and irreversible changes in key ecosystems. Greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, not fall. Heatwaves, floods, storms, glacial melting, sea-level rises, global hunger, displacement, migration, massive economic instability, public health disasters… it’s safe to say that, unless we get our act together fast, the forecast is grim.

You might think that an understanding of human sex differences is a strange angle into this planetary problem, but according to recent studies, it is essential. Researchers have known for decades that women are both more concerned about the environment and more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors than are men. Back in the 1980s, when these issues were tangled up mostly with nuclear scares, this sex difference was thought to have something to do with traditional gender roles. As primary caregivers, women’s environmentalism centered on the health and safety of their children, whereas men’s anxieties, as providers, were about another type of green altogether: money. Yet more recent work showed that even when you control for demographic variables, such as age, parenthood, education, and income, the sex difference remains robust.

Men are more likely to deny the problem of climate change altogether. Even those men who do accept the grave reality have more psychological barriers in adopting pro-environmental behaviors than do women, endorsing statements such as “I can’t change because I’m invested in my current lifestyle,” “Making this change would be criticized by those around me,” “There’s so much information out there that I am confused about how to make this change,” or “I’m already doing enough to make further change unnecessary.” Moreover, these sex differences in environmentalism pan out even when you factor out sex-linked personality variables (such as agreeableness and conscientiousness, which women score higher on and uniquely predict environmentalism). Above and beyond the Big 5, sex differences appear.

Rather, what has become increasingly clear is that the very concept of environmentalism has been oddly feminized. Many investigators suspect that, as a result, men’s recalcitrance in adopting pro-environmental behaviors is due in large part to a perceived threat to their masculinity.

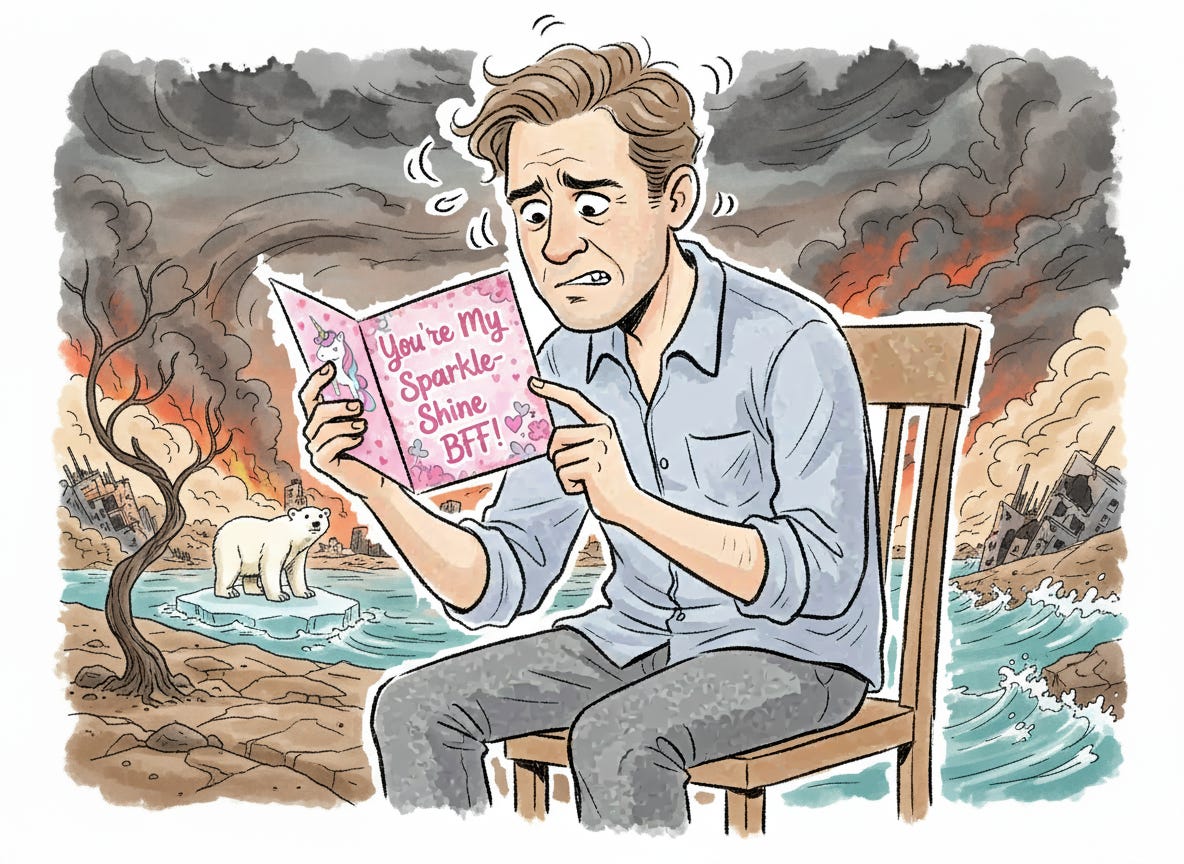

Nowhere is this psychological quirk on more troubling display than in the clever marketing studies of Aaron Brough and his colleagues, whose research addressed how gender stereotypes impact eco-friendly purchasing behaviors. In one experiment, for instance, male participants were told to imagine receiving a feminine-looking birthday card (think, I don’t know, frilly lace and pink roses) from a coworker, with a line inside saying “made me think of you.” Compared to a control group of men—who didn’t get such a girly card—these “masculinity-threatened” men were less likely to say they’d buy an eco-friendly product, choosing the nongreen option instead. But there’s a countermeasure. Brough’s work also found that when you give men a boost of masculinity, they’re suddenly more willing to buy green. For that study, men submitted a handwriting sample and were informed that an algorithm had found it particularly manly. These manly men (not really of course, it was just part of the study) were more likely than the men in the control condition to prefer an eco-friendly drain cleaner product. Only with their masculinity bolstered this way, in other words, were men willing to go green.

A separate study, this one from a different team of investigators, had participants rate the masculinity or femininity of people shown engaged in a variety of activities. When the person was shown doing a pro-environmental behavior, say, using a clothing line instead of a tumble dryer, opening windows rather than using air-conditioning, adhering to a vehicle maintenance plan, etc., they were judged as more feminine. Yet another finding revealed that men with more masculine faces and voices tend to hold less favorable pro-environmental attitudes, suggesting that testosterone may somehow play a role in this more general sex difference.

“Altogether,” write Jessica Desrochers and John Zelenski in a recent article in Current Psychology, “[such] studies suggest that environmentalism, in general, is viewed as feminine, and males may act less environmentally to protect their masculinity.”

At the very least, urgent climate-change initiatives seem to have something of a gender image problem, and given that the earth’s leaders are overwhelmingly male, you can see why this matter of sex differences deserves more than a trivial footnote. Bough, for his part, proposed redesigning green logos or products with more masculine fonts and colors. That couldn’t hurt. But at this late stage, it feels like trying to stop a flood with a sponge.

Maybe—and this is just me thinking while writing a sex and science column—we need to sex up the problem. Consider that although men seem to view environmentalism as a neutered trait, they’re also tacitly aware that, ironically, women are attracted to men who care about the environment. Going out of one’s way to minimize harm or even benefit the natural world signals prosocial qualities especially relevant to long-term pair bonding and coparenting. Studies indeed show that, all else being equal, women prefer “green men.”

From the male’s unconscious point of view, compromising one’s self-perceived masculinity for a piece of tail should be a literal no-brainer. Perhaps we should start appealing more to men’s base reproductive sensibilities (i.e., their evolved genetic motives) to effect climate change. It’s a pragmatic exercise, right? Whatever works. One vivid example of this Darwinian hack is a simple study by psychologists Daniel Farrelly and Mangal Singh Bhogal. Male and female participants (all straight, by the way) were told to imagine being approached by an investigator conducting a survey on sustainability practices. They were shown a large photo of this hypothetical investigator, below which read a brief message from that person: “Thanks for agreeing to participate, please answer the questions below!” Here’s an example:

“How often do you spend the time and effort to prepare household waste for recycling (e.g., cleaning plastic bottles and tinned cans or sorting paper and cardboard)”

The trick was that half of the participants saw a photo of an attractive male investigator, and half saw a photo an attractive female. (Three different male faces and three different female faces were used, so that the researchers could be certain any effect wasn’t due simply to one particular pretty face.) The results were striking. Participants who were asked these questions by an investigator of the opposite sex reported significantly more pro-environmental behaviors than those asked the exact same questions by someone of their own sex.

Farrelly and Bhogal acknowledge this could be nothing but false reporting about past behavior—a form of impression management, not unlike the empty rhetoric used by many politicians and other stakeholders to appear eco-friendly. Still, “it would be of immense value,” they write, “to see if mate choice scenarios do indeed lead to changes in actual future pro-environmental behavior, which could be assessed in… actual real-world [settings].”

Anyway, we may have to get really creative, but I’d say there’s an obvious takeaway message from these psychological studies. At this point, it might be easier to rebrand environmentalism as a manly enterprise than to reforest the Amazon.

Like what you read? Toss a tip in the jar—any amount that makes sense for you—so I can keep overthinking things on your behalf.